Musik für

Kinder

''Since the beginning

of time, children have not liked to study. They would much rather

play, and if you have their interests at heart, you will let

them learn while they play; they will find that what they have

mastered is child's play.''

The sparkling, gamelan-like

chimes heard on the Langley recordings emanate from Orff percussion

instruments. These simple mallet-struck melody-makers were invented

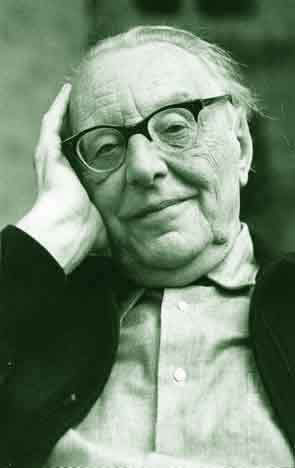

by German composer and educational theorist Carl Orff (1895-1982)

as elemental teaching tools. Orff believed that any child --

regardless of talent, cultural milieu, or physical constraint

-- could partake of the joys of playing music with little or

no traditional training.

Perhaps best

known as the composer of the scenic oratorio, Carmina Burana

(1937), Orff had long been a proponent of alternative music instruction.

He felt that the primal behaviors of children -- for instance,

clapping, chanting, banging out a beat, and dancing -- were better

educational building blocks than technical studies. He believed

that once children learned to appreciate fundamental music-making

through rhythmic activities and games, they could be taught to

read and write notation.

Orff and his associate Dorothee Günther founded, in 1924,

the Munich-based Güntherschule, where music, dance,

and gymnastics were taught. Gunild Keetman, who enrolled as a

student in 1926, eventually became Orff's partner in the evolution

of the Orff Schulwerk -- literally, "school work,"

but more specifically a focus on creative, educational activity

through speech, music and movement. The Schulwerk also

promotes cooperation and teamwork -- students are encouraged

to listen to each other, to hear what their neighbor is playing,

and to be conscious of the ensemble sound.

An outgrowth

of the Schulwerk was the development of an instrumentarium

on which students could express themselves rhythmically and melodically.

Orff drew on the delicate, enchanting Indonesian gamelan orchestra

and early African percussion for his diatonic and chromatic xylophones,

glockenspiels, and metallophones. These are augmented by an arsenal

of bells, hand drums, claves, resonator bars, jingle rings, temple

blocks, shakers and other rhythmic noisemakers. The simple-to-play

Orff instruments were designed to make the music-learning experience

fun and exploratory, while helping develop motor skills. Children

are taught to concentrate on repeated pulses and melodic patterns

(ostinato), and improvisation is encouraged.

Between 1950

and 1954, Orff and Keetman completed and published the five-volume

Music For Children, which codified their methodology,

and which subsequently sparked international advocacy. Today,

Orff organizations are based in the U.S. (85 chapters in all

50 states), Canada, most western and many eastern European nations

(including Russia and Poland), Australia, New Zealand, Japan,

Taiwan, the People's Republic of China, and South Africa. According

to the American Orff-Schulwerk Association, an estimated 11,000

U.S. teachers, to varying degrees, introduce youngsters to the

wonders of music using Orff techniques.

Orff melody

instruments heard on the Langley sessions include wooden xylophones

and metallophones (whose metal bars sustain resonance longer

than wood). A unique characteristic of this pitch percussion

is that bars can be removed from the tonal array, thereby guiding

children to hit the right notes. Consequently, as Hans Fenger

observed, "even a little kid can jam." In addition,

the Orff technique of "body music" is reflected in

the clapping and foot-stomping heard on "Saturday Night,"

"Rock Show," and "I'm Into Something Good."

What makes

the Langley project so unusual is that Orff techniques are not

generally performance-oriented; they are learning-focused.

Rather than being used to play "songs," the tuned percussion

often provides a "sound carpet" for vocalizing and

expressive movement. Even rarer is the use of the instrumentarium

to render contemporary pop; the Schulwerk instead encourages

the performance of indigenous folk music. There is a limited

repertoire of original compositions written specifically for

the instruments, such as Libby Larsen's "Song-Dances to

the Light" (whose score also includes conventional orchestral

instruments and chorus). Larsen also notes, "Philip Rhodes,

a very fine composer who taught for a number of years at Carleton

College in Northfield, Minnesota, has composed some very fine

work for Orff instrumentarium." Upper grades occasionally

use Orff percussion to improvise on the blues or jazz. But to

play songs by the Beach Boys, David Bowie, Fleetwood Mac and

the Bay City Rollers? To perform "Calling Occupants of Interplanetary

Craft"? Pretty much unheard of. Fenger did this in the mid-1970s,

but had to wait a quarter-century for a wider hearing.

In the Schulwerk,

Orff refrained from grand didactic strictures; he provided simple

formulas that would inspire teachers to exercise their own imaginations

in the classroom. Thus, Orff educational activities become learning

experiences for teachers as well as pupils. Certainly Fenger

-- who had some Orff training -- took these liberties to heart

in his selection of songs and his adventurous arrangements. As

he said, with a preceding demurral of modesty, "Every note

came out of my head."

Hermann Regener

wrote of the "timeless quality" of the Schulwerk,

adding that it "does not prepare one only for an understanding

of the classics or of medieval or contemporary music. [It] foster[s]

fundamental, general benefits of value to the whole person."

In the case of the Langley students, it is abundantly evident

that they performed these songs with body and soul.

For further information:

The

American Orff-Schulwerk Association (AOSA)

P.O. Box 391089, Cleveland, Ohio 44139-8089

(440) 543-5366

www.aosa.org

Carl

Orff Canada - Musique pour enfants

www.orffcanada.ca

Orff

Schulwerk Around the World:

check www.aosa.org web site for links