But New Yorker RICK GOETZ, who had become enamored of Taylor's scat stylings from a widely circulated WFMU cassette, swore to me in late Spring 2002 that he would locate Shooby. He phoned countless metro denizens named ''William Taylor'' throughout the five boroughs. Then, on July 16, Rick sent me an email:

I spoke to William Taylor Jr. today.

Shooby is alive, although he is in a hospital in NJ. Apparently

he just suffered a slight heart attack. William Jr. said he would

give my # to Shooby this Friday. He is 73 years old.

The Taylor offspring confirmed that his dad had pursued a quixotic career as a scat singer in New York City for decades, with no success. In 1992, Shooby moved to a senior complex in Newark (15 minutes from my home, and the city of my birth). Tragically, a 1994 stroke had silenced the scatman's musical prowess, and he no longer recorded or performed.

Goetz phoned Shooby, discovered that he was in a nursing home, not a hospital, and a date was arranged for a visit...

SUNDAY, JULY 28, 2002

Rick and I took Rt. I-280 West to Newark, got off at Clifton St., and drove a few blocks south to the Newark Health & Extended Care center on Jay Street. Strange neighborhood, for a once-densely populated urban area -- each block contained large vacant lots overgrown with greenery. Where homes and shops had proliferated to fill every inch of street frontage over the past 200 years, wilderness was reclaiming real estate. These lots didn't even sport "For Sale" signs.

Rick and I took Rt. I-280 West to Newark, got off at Clifton St., and drove a few blocks south to the Newark Health & Extended Care center on Jay Street. Strange neighborhood, for a once-densely populated urban area -- each block contained large vacant lots overgrown with greenery. Where homes and shops had proliferated to fill every inch of street frontage over the past 200 years, wilderness was reclaiming real estate. These lots didn't even sport "For Sale" signs.

We'd brought along a video camera, a DAT deck, a digital camera, and a boombox (to play Shooby his own music). The reception staff at the front desk were cordial, but house policy forbid bringing such equipment upstairs while visiting patients. We surrendered our audio weaponry, and were issued a visitor's pass for the third floor.

Rode up the elevator, and were directed to Room 333, where we found William Taylor lying prone on a bed, awake but staring at the ceiling, the Yankee game buzzing at low volume on a corner TV. The black man wore white dungarees and a pink cotton shirt over a white T. He seemed a bit south of 6 feet, of moderate build. Not much hair up top, but wisps of gray curled around the sides and back. The exposed shins between his trouser hem and socks were scaly, with dark blotches that betrayed a reptilian sheen.

Taylor was happy we'd come to visit, and quickly sparked to life. He'd been expecting his son William, Jr. to visit two days before, but WT Jr. was a no-show, and didn't call. This had lowered the elder Taylor's spirits. But he welcomed his two guests, and sat up in bed to get acquainted. He was outgoing and colorful, a relic with a legendary past, brimming with folksy wisdom and hosannas to Jesus. It was like meeting Satchel Paige.

Taylor had suffered a stroke in 1994, and his speech is sometimes hesitant (and sometimes not). He's also had heart problems, which prompted the East Orange VA to admit him to the nursing facility two weeks before. He maintains an apartment on Broad Street, Newark, where he's lived for ten years. (He claims he doesn't particularly like New Jersey, it's just where he lives. He considers himself a New Yorker at heart.) Taylor is semi-ambulatory. He can walk and stand gamely with or without a cane, but he mostly relies on his wheelchair -- sometimes valiantly pushing it from behind -- to get around.

He talked readily, was easygoing, but clearly not operating at 100%. We spoke for a while, exploring his fascinating personal history, all the while lamenting that tape (audio or video) wasn't rolling. Shooby suggested getting a pass from the front desk so we could drive him to his apartment, where he had to attend some personal business. He could show us tapes of his recordings, we could take pictures, videotape, and conduct an impromptu interview. As we helped him into his wheelchair, he donned a wild pink-and-white tiger-striped sports cap and an incongruous "Tommy Girl" shoulder pouch. I asked if we could call him "Shooby," and without hesitation he urged us to do so.

Staff at the front desk were reluctant to give him a pass. His admission papers listed WT Jr. as authorized guardian, and thus the only person who could give permission for Shooby to leave the premises. Staff tried calling William Jr., but got his answering machine. There was no one else to ask. Shooby said that besides his son, his "only other next of kin is Jesus Christ."

After determining that Shooby himself had registered his son's name as authorized guardian, we contended persuasively that he could reassign guardianship to us on a temporary basis. After conferral between departments, this procedure was OK'ed, and Shooby signed himself out in our care. With his wheelchair bulging from the trunk held firm with bungee cords, we drove downtown.

Along the way, Rick filmed from the back seat, and we plied Shooby with questions. The information below was elicited at the nursing home, in the car, and at his apartment.

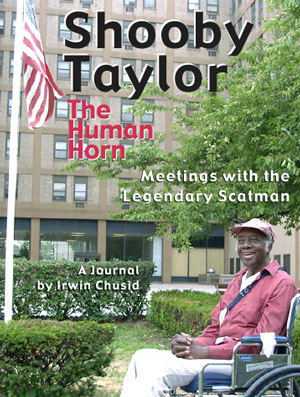

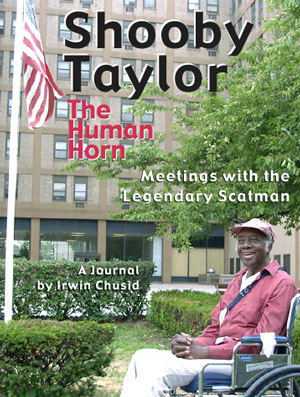

He lives in a sprawling senior complex across from Lincoln Park. After finding a visitor's space in the back lot, we engaged in a photo op at a circular garden near the building entrance. When we wheeled Shooby in the lobby, a number of residents extended hearty welcomes. He seems popular, and there is about him the undeniable warmth of the harmless, lovable, bemused old coot.

He lives in a sprawling senior complex across from Lincoln Park. After finding a visitor's space in the back lot, we engaged in a photo op at a circular garden near the building entrance. When we wheeled Shooby in the lobby, a number of residents extended hearty welcomes. He seems popular, and there is about him the undeniable warmth of the harmless, lovable, bemused old coot.

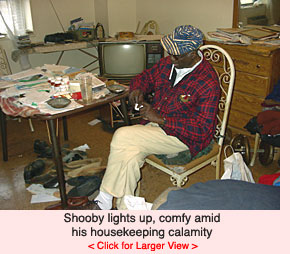

Taylor's 5th-floor efficiency unit is squalid and in disarray, a depressing bedsitter flat. A small kitchenette, sink piled with skanky dishes, was off the short foyer, which led into a combination living room/bedroom. There was a ubiquitous layer of grime; a Good Housekeeping Seal wouldn't have adhered to any fixture in the place. A bathroom was off in the corner. It was a hot day -- and hotter in his apartment. The windows were shut, stayed shut, and there was no A/C. It was very uncomfortable.

Dented, empty soda cans, mail, bills, encrusted cups, medical paperwork, and a torn bible were heaped on a small table -- the only table in the room. Also a few ashtrays, video boxes, and torn cellophane wrappers. Prescription drug bottles -- LOTS of them -- were clustered around the apartment: on the table, on a nightstand, on the window sill. Religious tracts, a Billy Graham booklet and gospel memorabilia were scattered about. Godliness abounded, but no cleanliness. The place was a soul-bleeding wreckage. He apologized, but we weren't there to marvel at his domestic skills.

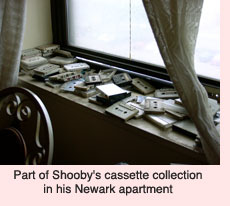

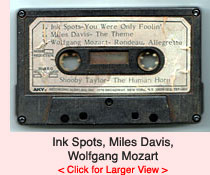

Two modest boomboxes -- one that also played CDs -- sat adjacent to scores of scruffy tapes strewn willy-nilly amid empty cases. Dozens more sat in the window, exposed to sunlight. They were dirty, some water-damaged; the handwritten labels were sun-bleached, or peeling. Many were of gospel artists, with a smattering of Jimmy Smith, the Mills Brothers, the Ink Spots, Billie Holiday, various jazz and pop artists, and preachers. A dozen or so of his own cassettes were equally exposed, and in various conditions of decrepitude. Some of his personal tapes had songs and artists listed, others just a single performer (e.g., "Johnny Cash"). These cassettes had been professionally duplicated, some with Shooby's name emblazoned on the plastic, but they were clearly low-budget productions and he only seemed to have one copy of each tape.

Two modest boomboxes -- one that also played CDs -- sat adjacent to scores of scruffy tapes strewn willy-nilly amid empty cases. Dozens more sat in the window, exposed to sunlight. They were dirty, some water-damaged; the handwritten labels were sun-bleached, or peeling. Many were of gospel artists, with a smattering of Jimmy Smith, the Mills Brothers, the Ink Spots, Billie Holiday, various jazz and pop artists, and preachers. A dozen or so of his own cassettes were equally exposed, and in various conditions of decrepitude. Some of his personal tapes had songs and artists listed, others just a single performer (e.g., "Johnny Cash"). These cassettes had been professionally duplicated, some with Shooby's name emblazoned on the plastic, but they were clearly low-budget productions and he only seemed to have one copy of each tape.

Rick told him that some of his recordings are on the internet, but Taylor didn't seem to understand the concept of the world wide web.

I told him he had an entire chapter in my book, and he was right proud.

He agreed to loan us three or four cassettes of material we hadn't heard, and insisted on keeping one for himself, which he pocketed. Rick intends to transfer these to digital, and then return them to Shooby with copies on CDR. Taylor was at first reluctant to give us all the tapes -- there were 10 or so with unheard material -- stubbornly insisting that "three is enough." But Rick and I, on the same wavelength, realized we couldn't assume a second visit (though we intended an imminent return), or that Shooby's health would sustain, and had to seize our best opportunity to collect and preserve as much of Shooby's recorded legacy as possible. Finally, he seemed to grasp our sincere intent, and relented, allowing us to take all tapes except the one in his pocket.

He agreed to loan us three or four cassettes of material we hadn't heard, and insisted on keeping one for himself, which he pocketed. Rick intends to transfer these to digital, and then return them to Shooby with copies on CDR. Taylor was at first reluctant to give us all the tapes -- there were 10 or so with unheard material -- stubbornly insisting that "three is enough." But Rick and I, on the same wavelength, realized we couldn't assume a second visit (though we intended an imminent return), or that Shooby's health would sustain, and had to seize our best opportunity to collect and preserve as much of Shooby's recorded legacy as possible. Finally, he seemed to grasp our sincere intent, and relented, allowing us to take all tapes except the one in his pocket.

He was friendly throughout our visit, though an obstinate streak surfaced periodically. At one point he bristled when I reached for the deck's "Play" button, and tried to shoo me away, asserting, "I'll handle that." He relaxed on the control issues after a while. He might have been feeling the heat, or exhaustion from such uncommonly stimulating activity.

Taylor betrayed bitterness about the way he'd been treated by musicians and music business people over the years. He had not been taken seriously, and had to struggle all the way. He called this "paying your dues." Yet he was undaunted, and proud of his work. The ridicule and rejection did not dissuade him from his destined form of creative expression, which he described often as "a gift." He emphasized that he "practiced" his art, and developed his style and original vocal language on his own (with inspiration from quirky bebop legend Babs Gonzales).

I brought along a copy of my book, Songs in the Key of Z , to give him. However, I reconsidered and instead asked him to autograph the copy. He consented, and painstakingly wrote "Shooy Taylor." He began to scrawl the date as "6-28-," when I reminded him that July was the seventh month. He crossed out "6" and wrote "7" before it. After he handed me back the book, I explained that he'd deprived me of a "b" in his first name, so he corrected his printing. The autograph is a mess, but it's authentic. I had to keep that copy and promised to mail him another later that week. He signed Rick's book, and having practiced on mine, did so flawlessly.

We spent over three hours with Shooby. At several points he stressed that our visit was the best thing that had happened to him in some time. We jolted a consciousness that had been dormant. He hadn't sung or performed in years, and patients and staff at the nursing home and residents in his apartment building had no clue about his past.

Biographical information elicited during our conversations:

-

>° William H. Taylor was born in Indiana Township (Allegheny County), PA, on September 19, 1929. His family brought him to New York when he was 18 months old. He grew up in Harlem, and considers himself a New Yorker.

-

>° As a youngster, he had been embarrassed about stuttering, and consequently didn't finish high school.

-

>° He married a woman from Harlem named Sadie (nickname: "Peaches"); they had a son, William H. Taylor, Jr., born when Shooby was 17. He and Sadie were divorced, he didn't say when. They remained friends, but she passed away in the 1980s.

-

>° He entered the military in 1953, and was training in Augusta GA for assignment to Korea when the war ended. He was discharged in 1955.

-

>° He worked for the post office in New York, at several locations, and at several positions, but never as a letter carrier.

-

>° Growing up and on into adulthood, he listened to and admired Ellington, Miles, Ella, Sarah, and countless other jazz icons. (Curiously, I don't think he mentioned any saxophonists.) He heard sounds in his head and felt destined to express them musically. He went to music school, practiced saxophone, and tried to master the instrument, but to little avail. Then, an epiphany: he was foolish to try and convey his musical soul through an instrument, because, he realized, "I am the horn!" He began developing his idiosyncratic scat style -- not to imitate a horn, but because voice was his instrumental "gift." He did admit to playing "air saxophone" when he performed and recorded.

-

>° His idol was jive scatmaster Babs Gonzales, whom Shooby tried to emulate. He met Babs once, and claims to have gotten permission to use the name "Shooby" from Dizzy Gillespie. He asked Diz personally, and Diz approved of the moniker.

-

>° He estimated paying about $30/hr studio time at Angel, and elsewhere. He mentioned a facility on 23rd Street, but couldn't recall the name.

-

>° The fellow who played Farfisa organ on "Stout-Hearted Men" (heard on Songs in the Key of Z, Vol. 1) and a few of his other recordings was a session jazz keyboardist, Freddie (or Freddy) Drew, of the Bronx, who has since passed away.

-

>° Shooby'd been a boozer. BIG drinker, he stressed. Cleaned up through AA, and Jesus.

-

>° I asked him how he'd been "with the ladies." Admitted he'd been a "fornicator" and a "whoremonger," but no longer. Since he didn't say when his marriage ended, we don't know if his carousing coincided with his marriage, led to his divorce, or happened after his divorce.

-

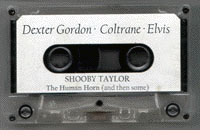

>°  He tried to perform at the Apollo, but was booed offstage. He attended countless jam sessions at NYC clubs, but was rarely given the chance to wail. He was not taken seriously, was scorned, and made to feel unwelcome. But he would not quit. He financed his recordings to prove his artistry. In addition to vocalizing over the Ink Spots, the Harmonicats, and country gospel singer Christy Lane, he dubbed his "Shoobology" over Johnny Cash, Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Shirley Caesar, Errol Garner, and Elvis -- among others. Mozart, for God's sake! Shooby Taylor, scatted over Mozart's Rondeau Allegretto.

He tried to perform at the Apollo, but was booed offstage. He attended countless jam sessions at NYC clubs, but was rarely given the chance to wail. He was not taken seriously, was scorned, and made to feel unwelcome. But he would not quit. He financed his recordings to prove his artistry. In addition to vocalizing over the Ink Spots, the Harmonicats, and country gospel singer Christy Lane, he dubbed his "Shoobology" over Johnny Cash, Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Shirley Caesar, Errol Garner, and Elvis -- among others. Mozart, for God's sake! Shooby Taylor, scatted over Mozart's Rondeau Allegretto.

-

>° He last publicly performed in a bar on West 23rd Street in 1993. He can't recall the name.

-

>° Around 1995, The David Letterman Show, who had obtained a cassette of Taylor's recordings from the WFMU catalogue, tracked down the scatman and invited him to appear on the show. However, Shooby was recovering from his stroke and told the show's coordinators that he could no longer sing. He politely declined the invitation.

-

>°  He radiated a sense of vindication that now, in his twilight years, two "youngsters" showed up on his doorstep to tell him that people all over the world were listening to his music, and that we were interested in preserving his artistic legacy.

He radiated a sense of vindication that now, in his twilight years, two "youngsters" showed up on his doorstep to tell him that people all over the world were listening to his music, and that we were interested in preserving his artistic legacy.

-

>° He claims to have the original open-reel tapes of his sessions, tucked away in a closet. He has no idea what condition they're in. All the more reason to preserve those cassettes.

-

>° He goes to church regularly.

-

>° He insists he will never perform again. "The gift" is gone.

-

>>Read two at-home Interviews< <

MONDAY, AUGUST 5, 2002

Spoke with Shooby on the phone.

A propos of nothing, he exclaimed: "That tape with Dexter Gordon -- that's a masterpiece!"

A propos of nothing, he exclaimed: "That tape with Dexter Gordon -- that's a masterpiece!"

Said he tried calling Rick twice yesterday, but got a recorded message intoning, "The party you are calling has a blocked number." He didn't know why that happened, because he always pays his phone bills. "I love paying bills," he proclaimed.

Said he would be in physical therapy today, and his son would visit later.

I had shipped him my book Songs in the Key of Z. He enjoyed his chapter, though he identified two erroneous pieces of information. Understandable, I conceded, since we didn't have him to fact-check before publication.

1) BOOK: "Shooby apparently is -- or was -- a resident of Brooklyn." This was based on a (faulty) recollection by Craig Bradley, one of the studio engineers present at Taylor's Angel Sound sessions.

SHOOBY corrects: "I lived in Harlem my entire life. I am a New Yorker!" (He was actually born in Pennsylvania.)

2) BOOK: Bradley is quoted as saying, "He once told me he got beat up by a woman in a laundromat for being a little too forward. She smacked him around."

SHOOBY clarifies: "The woman attacked me, and I lowered the boom on her. So they called for an ambulance on her. They took her to Harlem Hospital for stitches. They arrested both of us. I said I didn't want to press charges, unless she did. She didn't press charges, so I didn't press charges."

He reiterated that he was grateful to us for helping to preserve his music.

SUNDAY, AUGUST 11, 2002

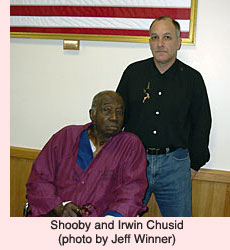

Visited Shooby for a couple of hours with my buddy Jeff Winner. This time, the front desk didn't confiscate our equipment -- or even ask to see it. They let us go upstairs with unchecked bags.

Visited Shooby for a couple of hours with my buddy Jeff Winner. This time, the front desk didn't confiscate our equipment -- or even ask to see it. They let us go upstairs with unchecked bags.

Found Shooby in bed, under headphones attached to a Walkman, listening to a tape of himself. From a prone position, he welcomed us brashly with handshakes, while keeping the headphones on. He'd been to church that morning.

He told us that he'd taken a fall recently and hurt himself. He remained in bed on his back while conversing.

Recorded him on DAT for about 45 minutes. Mostly autobiography. He rambled, wasn't very focused.

"When I lived in Harlem, I used to go down to Battery Park and scat -- to anyone who would listen, but mostly for myself. Summer and winter. For winter, I'd wear long johns. They had a McDonald's and a deli nearby, and they got to know me. During winter, I'd get warmed up, get a sandwich, then I'd come back out and scat til I got cold again."

More: "I don't love Jersey. The reason I moved to New Jersey was, I used to stay at the Robert Treat Hotel [in downtown Newark] under the name 'William H. Taylor.' I gave the proprietor a sample of my music, and he was intrigued. He said, 'What kind of language is that?' I said, 'It's scat! Something I feel, something I can do'."

More: "I don't love Jersey. The reason I moved to New Jersey was, I used to stay at the Robert Treat Hotel [in downtown Newark] under the name 'William H. Taylor.' I gave the proprietor a sample of my music, and he was intrigued. He said, 'What kind of language is that?' I said, 'It's scat! Something I feel, something I can do'."

Said he'd recorded in at least two studios, but couldn't remember their names. Wasn't sure if Angel Sound was one of them.

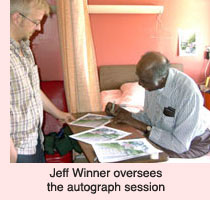

Gave Taylor a print of a beautiful 8"x10" of himself, beaming a big smile, sitting in his wheelchair in the courtyard outside his Newark apartment building, with the American flag waving nearby. Asked him to autograph ten copies of that pic. He sat up to do so, but it was a painstaking routine, requiring two minutes to sign his name to each photo (about 20 minutes total). Jeff held the photos in place, while I spoke to staff at the third floor front desk.

Gave Shooby a CDR of three songs from the cassette I'd borrowed. The jewel case was adorned with a photo taken in his apartment last visit.

Gave Shooby a CDR of three songs from the cassette I'd borrowed. The jewel case was adorned with a photo taken in his apartment last visit.

He offered to lend two more tapes -- including the one he refused to part with last time -- in exchange for the one returned. However, he'd given the second tape to the downstairs daytime receptionist (Gloria MacMurray), who, by the time I went looking for her, had left for the day. The second shift receptionist called MacMurray at home, and MacMurray said she had the tape ("Got it right here. It says 'Scooby' [sic] Taylor."). She offered it to me in the interest of preserving Taylor's work, and said to drive by her apartment in East Orange afterwards to pick it up.

We listened to a tape. Some great stuff -- a weird country song, jazz jams with an organist (he couldn't remember who -- turned out to be Charles Earland), a great scat workout with his hero Babs Gonzales, a male-female vocal duet, many more country tunes, some gospel, and a funky Miles Davis number. Very good audio fidelity.

We listened to a tape. Some great stuff -- a weird country song, jazz jams with an organist (he couldn't remember who -- turned out to be Charles Earland), a great scat workout with his hero Babs Gonzales, a male-female vocal duet, many more country tunes, some gospel, and a funky Miles Davis number. Very good audio fidelity.

Shooby re-emphasized, "I was a fornicator. But I was a good fornicator." (Jeff later observed that it adds new meaning to "The Human Horn.") Shooby again stressed that he doesn't do that kind of thing anymore.

Made plans to visit him on Friday August 30 with filmmaker Doug Stone. Shooby told us he has dialysis treatment on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. I also expressed my hope to bring him down to WFMU for an on-air interview later in the month.

After our visit, Jeff and I drove to East Orange to pick up the second tape at MacMurray's. She said she didn't need it back, and that we should "give it to Mr. Taylor." Very nice lady.

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 14, 2002

Spoke with Gloria MacMurray ("like Fred," she said), the receptionist at Shooby's nursing home. Explained our plans to film and interview Shooby, and wanted to make sure our repeated visits wouldn't intrude on the residents and staff. She passed along everything to Veronica Anonyuo, the facility's Head of Social Services, who said they're cool with what we're doing, and that no letter of intent would be necessary. Gloria reiterated that no cameras are allowed upstairs, but that we could film downstairs as long as Taylor agrees, and that taking him out of the facility with his permission is permitted.

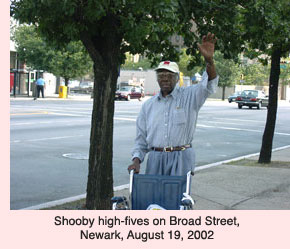

MONDAY, AUGUST 19, 2002

Went to visit Shooby to return his cassettes and pay my respects. He offered to take me out for lunch. I wasn't hungry, but didn't want to refuse his obvious generosity and desire to hit the streets. He wore a sports cap with "Canada" across the brow. Got it from his nurse, Conserve, who had recently vacationed up north. He liked Conserve, who entered the room during our conversation to change the bedding for Shooby's roommate.

Shoob took his wheelchair, but refused to sit in it -- he pushed it for balance, shuffling slowly down the hall. He chatted jovially with staff and other residents in the corridors. I signed him out at the 3rd floor desk, and we took the elevator down to the admissions floor. He waited while I fetched the car, standing dutifully behind his wheelchair as if pushing an imaginary patient. I drove up and he gingerly climbed in the front seat, while I collapsed the wheelchair, swung it in the trunk and hooked bungees. Shooby instructed me to drive to Broad Street, Newark, to a particular eatery a block or two from his apartment building.

In the car, he asked if he could smoke. No problem, I told him. I was surprised that he indulged. Said he only did so outside the nursing home.

In the car, he asked if he could smoke. No problem, I told him. I was surprised that he indulged. Said he only did so outside the nursing home.

We parked in a commercial lot and crossed the street to Palace Fried Chicken (cor. Broad and Chestnut), a cheap & dirty fast food joint with fluorescent lighting, plastic booths, and protective Plexiglas separating customers from counter help. The illuminated wall menu above the counter displayed color-faded photos of burgers, hot dogs, fried chicken, corn on the cob, mozzarella sticks, whiting sandwiches, hot wings, cheese steaks, and gyros. Nothing looked appealing -- seafoam green was the dominant color in these pics -- so I ordered a side of slaw and bottled water. Shooby ordered a gigantic cheeseburger, of which he only took three bites during our subsequent conversation. The slaw looked older than Taylor's shoes, and was about as appetizing.

He talks loud, and without self-consciousness. He's naturally boastful, and proud. "I want to be heard. That's the show business."

He talks loud, and without self-consciousness. He's naturally boastful, and proud. "I want to be heard. That's the show business."

"Music is where I'm at," he exclaimed. Helps him find redemption. "Salvation," he noted. "But the most important thing is serving Jesus." He used to scat along with spirituals because he "felt it."

Taylor attended the Hartnett Music School (or National Music Studios -- 8th and 46th Street?) under the GI Bill. Studied with a voice coach. He tried writing music in school, but didn't stick with it. His thing was scatting. One time after work, he was walking up the front steps of the school. "Climbing the stairs, I could feel it. Those guys were wailing, man! I went into the room where the guys were jamming. I started scatting." His voice teacher heard him, and warned her charge that singing like that would "ruin your voice." But Shooby realized he could express himself better by scatting than by singing. "It was the right decision," he pointed out. "You have the evidence."

He used to tip the scale at 230, now weighs 160. But all that heft didn't help "the power of the singing," he said. "It's the feeling."

Was his son musical? "He tried bongos, but that was a long time ago."

After 21 years with the Post Office, he stopped working in the 1960s or '70s after getting hurt on the job (details unexplained). He still collects a pension. "The Post Office was good to me. I could've been fired." He confessed to having had a temper. "I blowed up on the job. They grabbed me and held me down. They wanted to know what was wrong with me. I learned I was going to a therapist. 'William H. Taylor -- he's a patient of ours.' I was messin' up things. I went in the big boss's office. I wanted a transfer, but they didn't want to give me one. They liked me and wanted me to stay. But I wanted to make 30 years. I blowed up to call attention to myself. It was a stupid thing to do. I was seeing a therapist."

Why was he seeing a therapist?

"Emotional problems." Once a month. "Not fights. I didn't run away from anyone. But I wasn't a fighter -- I was a lover!" The intro line, "You lied -- you bitch!" before his recording over the Ink Spots' "You Were Only Fooling," he said emerged because, "I was Romeo with the ladies." He often alludes to females who "won't leave [him] alone." He elaborated on his whoremongering: "I always paid for it. You find 'em all over. Not just in Harlem -- downtown, the Bronx -- come on, man!" Now that's over because, "I'm seeking God. I was trying all the time for God. I'm still trying."

"Emotional problems." Once a month. "Not fights. I didn't run away from anyone. But I wasn't a fighter -- I was a lover!" The intro line, "You lied -- you bitch!" before his recording over the Ink Spots' "You Were Only Fooling," he said emerged because, "I was Romeo with the ladies." He often alludes to females who "won't leave [him] alone." He elaborated on his whoremongering: "I always paid for it. You find 'em all over. Not just in Harlem -- downtown, the Bronx -- come on, man!" Now that's over because, "I'm seeking God. I was trying all the time for God. I'm still trying."

He recorded at a studio on 48th Street, but cannot recall the name. "They moved to 49th Street. Now he [the owner]'s in a new building."

He took the cheeseburger, shuffled back to the window and asked the server to pack it for the road. We slowly made our way across the busy, mid-afternoon Broad Street traffic, and drove back to the nursing home.

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 28, 2002

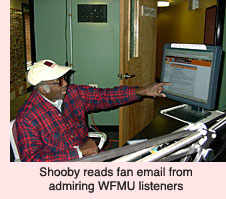

[For several weeks, I made arrangements for Shooby to appear on Ken Freedman's Wednesday morning WFMU program. The interview was contingent on Shooby's health on the planned date. He was scheduled for minor surgery on the preceding Tuesday, but it was postponed, so he indicated he was prepared to visit the station. The radio interview would be filmed by Doug Stone, who directed the BJ Snowden documentary, Angel of Love, and co-produced the outsider media cult film How's Your News. Stone and his cameraman Phil O'Brien also captured footage of Taylor at the nursing home before and after the radio appearance.]

The Big Day.

The Big Day.

Doug and Phil videotaped Shooby's triumphant departure from the nursing home, during which Taylor invoked God and Jesus numerous times in an impromptu benediction-cum-victory speech. The staff added their blessings for the impending interview, and bid him bon voyage.

While driving to the studio, I tuned in WFMU. Through the static (my aerial is a bent coat hanger), Shooby heard Freedman air his recording of "Tico Tico." Taylor smiled with dignified satisfaction, as if beholding a radiant sunrise.

While driving to the studio, I tuned in WFMU. Through the static (my aerial is a bent coat hanger), Shooby heard Freedman air his recording of "Tico Tico." Taylor smiled with dignified satisfaction, as if beholding a radiant sunrise.

When Shooby arrived at the station, it marked the first time in his life he'd been invited on radio, and the first time he'd been interviewed anywhere. He bore a particular grudge against Newark jazz outlet WBGO; he claimed that after speaking to an air staffer, they would not respond to his tape submission. Now, after years of rejection, scorn, frustration, and non-recognition, he felt vindicated.

>> The WFMU Program - Shooby speaks: Listen to interview & newly-discovered music here! (RealAudio)

We listened to Taylor's recordings, asked questions, fielded listener phone calls, and applied the Smithsonian luster. During the interview, I ran down the medical litany: the stroke in '94; the heart attacks; the thrice-weekly dialysis. No one knows Taylor's chances of making it to age 74, so I urged listeners to pay birthday (Sept. 19) respects to an American original by mailing cards and letters c/o the station. Learning that he has fans all over the world has been the greatest late-life gift, and he is very, very proud.

We listened to Taylor's recordings, asked questions, fielded listener phone calls, and applied the Smithsonian luster. During the interview, I ran down the medical litany: the stroke in '94; the heart attacks; the thrice-weekly dialysis. No one knows Taylor's chances of making it to age 74, so I urged listeners to pay birthday (Sept. 19) respects to an American original by mailing cards and letters c/o the station. Learning that he has fans all over the world has been the greatest late-life gift, and he is very, very proud.

I followed Ken on the air at noon, so Doug and Phil drove Shooby back to the nursing home, where they filmed another half-hour in the dining room. Doug hopes to provide some rough edited footage in a couple of months, and plans a documentary. He intends to track down the Live at the Apollo TV performance by Taylor that several people claim exists.

I followed Ken on the air at noon, so Doug and Phil drove Shooby back to the nursing home, where they filmed another half-hour in the dining room. Doug hopes to provide some rough edited footage in a couple of months, and plans a documentary. He intends to track down the Live at the Apollo TV performance by Taylor that several people claim exists.

The Outsider Music List is buzzing about the interview. They've posted links and are quoting their favorite sound bites.

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2002

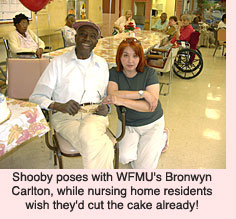

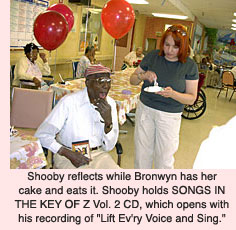

Tomorrow, September 19, is Shooby's 73rd birthday. After my program, WFMU staffer Bronwyn Carlton and I brought Shooby a 16" cake (from Riviera Bakery & Café, Hoboken), inscribed:

Tomorrow, September 19, is Shooby's 73rd birthday. After my program, WFMU staffer Bronwyn Carlton and I brought Shooby a 16" cake (from Riviera Bakery & Café, Hoboken), inscribed:

Happy 73rd Birthday Scat-Man! We love you SHOOBY!

Also brought a printout of several dozen well-wishing emails from listeners, 15 birthday cards that arrived from around the world (including Nebraska, Minnesota, SF, Holland, and Germany), and a bouquet of flowers purchased by Bronwyn.

A health care aide brought out a dozen, colorful "Happy Birthday" balloons already inflated and ribboned. Another staffer set out paper plates, plastic forks, and American flag paper napkins. We had everything we needed -- except the guest-of-honor.

Shooby was expecting us, but had gone to the first floor. Two aides fetched him from downstairs, and he rode the elevator up to the 3rd floor party room. When he emerged and wheeled himself into the dining area, the residents sang a geriatric "Happy Birthday," and the Scat-Man was deeply touched. Bronwyn and I attached several balloons to a chair, declared it the guest-of-honor's "throne," and sat him in it.

Shooby was expecting us, but had gone to the first floor. Two aides fetched him from downstairs, and he rode the elevator up to the 3rd floor party room. When he emerged and wheeled himself into the dining area, the residents sang a geriatric "Happy Birthday," and the Scat-Man was deeply touched. Bronwyn and I attached several balloons to a chair, declared it the guest-of-honor's "throne," and sat him in it.

Bronwyn did the cake-cutting (Shooby politely declined the task), and we passed slices to residents and staff around the dining room. We had to withhold cake from a few eager-faced residents after being advised by staff that they were diabetic. Shooby insisted on a monstrous-sized wedge, which made my eyes bug out. He didn't finish but a third of it, though, and later asked that it be wrapped and brought to his room.

Bronwyn did the cake-cutting (Shooby politely declined the task), and we passed slices to residents and staff around the dining room. We had to withhold cake from a few eager-faced residents after being advised by staff that they were diabetic. Shooby insisted on a monstrous-sized wedge, which made my eyes bug out. He didn't finish but a third of it, though, and later asked that it be wrapped and brought to his room.

I gave him the new Songs in the Key of Z Vol. II CD, which features Shooby's "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing" as the leadoff track. He autographed a napkin for Bronwyn, and painstakingly wrote out for her some scat syllables.

I gave him the new Songs in the Key of Z Vol. II CD, which features Shooby's "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing" as the leadoff track. He autographed a napkin for Bronwyn, and painstakingly wrote out for her some scat syllables.

I asked if he wanted to open the cards from listeners, but he insisted on reading them later in the privacy of his room. He said that next visit he would give me the envelopes to send thank you notes to those who were nice enough to correspond. He is not capable of writing letters, which would be an arduous task.

MONDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2002

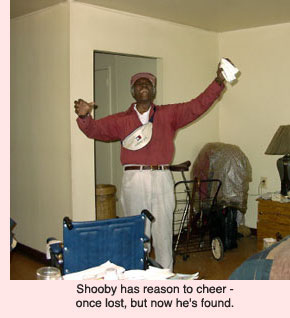

[Shooby had been discharged from the nursing home during the final week of September. I was in Minneapolis visiting my girlfriend, when he left a message on my machine. Said he'd requested the discharge, and it was granted. I was surprised at this development. He was back at his apartment on Broad Street. We spoke on the phone, and I promised to visit him upon my return.]

Over the past few days, I'd left two messages on Shooby's answering machine. Although he can no longer sing or scat, his outgoing message concluded with: "shooba-looba-looba-looba." (He later explained that this message was recorded ten years ago, before the stroke.)

Today I finally succeeded in reaching Shooby. He was agitated, rambled his way through a conversation, doing most of the talking, often raising his voice for emphasis.

Said that he and his son agreed that he needs to return to the nursing home for a while longer. The dialysis-related operation (to implant a shunt in his arm to facilitate the procedure) that had been postponed last month is being re-scheduled. However, before surgery the VA hospital needs to re-administer tests they conducted several months ago -- chest X-Ray, EKG, etc. -- because it's been too long since the last round. Shooby said he also might need a hernia operation, and has an appointment with the foot clinic. He was very anxious about these circumstances.

"I've got a very busy month," he explained, several times. Then he launched into a defiant diatribe: "Hey listen, I got a gift to give to the world -- my music. Not to you, but to the world! That's why I call myself 'Shooby Taylor, the Human Horn'! Because I got feelings like everyone else! I'm talking about the nursing home, the people where I live. They expect a lot from me. They expect me to laugh all the time? Sometimes I don't speak, because I already spoke when I came in. I got a personal life! I'm not yelling at you or Rick or my fans at the radio station -- but at people who don't think I'm human. I'm the Human Horn!"

I had no idea what he was driving at, but didn't take it personally, and don't think he intended it as such.

He was expected back at the nursing home later that afternoon, so I offered to drive him. Said I had another load of mail and birthday cards, and some tapes to return. He agreed, and sounded grateful. Then he resumed his diatribe.

When I arrived, Shooby was in an ornery mood. He sat at the card table-cum-landfill, chain-smoking Now cigarettes, the Dave Brubeck Quartet with Jimmy Rushing percolating on the CD deck. He was in no hurry to return to the nursing home, and picked up the tirade where he'd left off on the phone. "The music is a gift. Whatta you want from me? What do these people want from me? I don't do the music anymore. I have my life. You have the music." One cigarette extinguished, another lit. "I'm the artist. You're the producer. The music's there. I don't do it anymore. I had a stroke. I got a lotta problems."

When I arrived, Shooby was in an ornery mood. He sat at the card table-cum-landfill, chain-smoking Now cigarettes, the Dave Brubeck Quartet with Jimmy Rushing percolating on the CD deck. He was in no hurry to return to the nursing home, and picked up the tirade where he'd left off on the phone. "The music is a gift. Whatta you want from me? What do these people want from me? I don't do the music anymore. I have my life. You have the music." One cigarette extinguished, another lit. "I'm the artist. You're the producer. The music's there. I don't do it anymore. I had a stroke. I got a lotta problems."

He recounted his medical travails -- the dialysis, the feet, the heart, the implant operation. He didn't have his wheelchair in the apartment; he'd gone home with only a wooden cane.

I asked if he had any photographs from his younger days. This provoked his ire anew. "I don't have any. That's not now. All you have is the music. There are no photographs." He attempted to elaborate, but his explanation -- which I don't recall -- was a non-sequitur. There were no photographs, he reiterated impatiently.

While I sat on the bed, listening, I glanced down at some wrinkled yellowed papers, and a color photograph of 1960s or '70s vintage. Two black men in pin-striped zoot suits and felt hats -- a burly bruiser with a playful headlock around a pint-sized pal. I didn't recognize Shooby as either. I flipped the photo, but the reverse was blank. Curious, I was, but didn't want to further agitate the Human Horn by asking him about this photo after he'd vehemently denied the existence of same. It wouldn't have been polite.

I gave him a shopping bag stuffed with birthday cards, letters and postcards from WFMU listeners, and returned a few of his cassettes. He was grateful.

I asked if he had the open reel tapes of his original sessions. He flared again: "Yes. But I'm not in a mood to look for them." I asked why he was giving me such a hard time, and he explained that it wasn't me, it wasn't Rick, it wasn't his fans. It was "the people who want so much of me." I have no idea who those folks are -- the social workers? The doctors? His neighbors in the apartment building? He wasn't specific. He's allowed to behave in an erratic manner. He's Shooby Taylor, the Human Horn. He's had a stroke, and the medical community is proposing all manner of indignities.

Looking through the clutter, I discovered a CDR dated 1984 -- presumably from one of the studios where he'd recorded. It contained titles without artists, but there were enough clues to provide missing information about some of the recordings we'd previously preserved on CDR. In particular, the Charles Earland ("Blues for Rudy") and Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis and Johnny Griffin ("Gigi") tracks were now ID'ed.

While I poked through the cassettes and CDs, he seemed annoyed.

"You come here for the music. You look through the CDs and the tapes. But you don't even say anything about my apartment."

"What should I say?"

"It's a mess. You can see that."

"Uh-huh. So?"

"Why don't you say something about it?"

"Like what -- 'Shooby, clean your room?"

"Yeah."

"Why? I'm not your mother. Maybe you like this mess. Maybe you're comfortable living this way. I wouldn't be, but I know some people who seem perfectly at home buried knee-deep in their own crap. It's not my job to tell you to clean it up. Do you want me to help you? If you want me to, I will."

He nodded, as if to say, let's drop it. Point made. He wasn't interested in rearranging the mess. He just felt like venting.

He insisted on listening to the Johnny Cash/Shooby tape, which he termed a "masterpiece." I inserted the tape and hit "Play." He preferred it LOUD. He listened and talked, but the music was so blaring I could scarcely hear a thing he said. Taylor pointed out that these had been hits for Cash, and referred to several songs as "classics." However, it was apparent that the "classic" designation applied more to Shooby's scat overdubs than to the Man in Black's vocals or the songs themselves. After Cash, on the same tape, he ID'ed Shirley Caeser's "No Charge" (which I had mistakenly guessed was early Tina Turner).

He insisted on listening to the Johnny Cash/Shooby tape, which he termed a "masterpiece." I inserted the tape and hit "Play." He preferred it LOUD. He listened and talked, but the music was so blaring I could scarcely hear a thing he said. Taylor pointed out that these had been hits for Cash, and referred to several songs as "classics." However, it was apparent that the "classic" designation applied more to Shooby's scat overdubs than to the Man in Black's vocals or the songs themselves. After Cash, on the same tape, he ID'ed Shirley Caeser's "No Charge" (which I had mistakenly guessed was early Tina Turner).

About 45 minutes and seven cigarettes later, we prepared to leave the apartment. Before driving back to the nursing home, he wanted to buy me dinner at a seafood eatery down the block. I declined the offer, but said we could stop in to get him a meal. I tied up a plastic sack of garbage, and he threw some belongings in a bag. After locking up, he shuffled s l o w l y down the hallway, holding onto the corridor rail. A female neighbor came along heading the opposite way. "How are you, my dear?," he exclaimed, flashing a smile. She smiled back. "Never stop praying," he bellowed as she passed. After we took the elevator, I left him to walk slowly towards the front entrance while I went around back to fetch the Toyota. I drove around to Broad Street, and helped him into the passenger seat. He paused before sitting down, and said, "Irwin, I apologize for the way I was upstairs. I hope nothing I said hurt you." I assured him that I understood his frustration, and that everything was OK.

Two blocks down was the Newark Seafood House at 1011 Broad. Bright fluorescent lights, and too much empty space -- Shooby said the place used to be a grocery store, but opened as a restaurant a year ago. The premises were filled with an odd array of juxtaposed merchandise. Seafood -- cooked dishes, and fresh and frozen take-home -- along with display cases of stuffed animals, dime candy, Du-Rags, scarves, vials of ginseng extract, cheap jewelry and baseball caps. Anything to pay the lease, I guess.

Two blocks down was the Newark Seafood House at 1011 Broad. Bright fluorescent lights, and too much empty space -- Shooby said the place used to be a grocery store, but opened as a restaurant a year ago. The premises were filled with an odd array of juxtaposed merchandise. Seafood -- cooked dishes, and fresh and frozen take-home -- along with display cases of stuffed animals, dime candy, Du-Rags, scarves, vials of ginseng extract, cheap jewelry and baseball caps. Anything to pay the lease, I guess.

Shooby ordered a "fish sandwich" -- a vague request which meant something specific to the fry cook. Into the deep fryer sank some generic piece of breaded ex-marine life. The cook plopped the golden fried filet on two slices of bread, tossed it on a tray and passed it across the counter. Shooby slathered it with ketchup.

We walked over to an empty booth and sat for ten minutes while he ate. We chatted, I snapped pictures, and he was in a far better mood.

We walked over to an empty booth and sat for ten minutes while he ate. We chatted, I snapped pictures, and he was in a far better mood.

When I took him up to his room at the nursing home, he seemed "at home." He commented that he felt comfortable here, because the people treated him better.

I hadn't eaten for hours. He offered me a miniature Mounds candy bar from his windowsill, which I accepted. Only after unwrapping it did I realize it had melted one afternoon in direct sunlight, and re-solidified at evening into a mushy latke.

Shooby expressed gratitude for everything -- the ride, the friendship, the birthday cards, for Rick discovering him, for Jesus. As I left, he had a huge smile on his face.

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2002

morning - phone call

Shooby called. The previous Tuesday, he'd gone to the VA hospital for his dialysis treatment. However, the docs found an infection and would not release him.

He said: "I had to express myself to the nurse. The treatment is for four hours. After two hours, I wanted to stop. I told that to the nurse. She said she would tell the doctors. The doctor came to me and said, 'What is your problem? What are you talking about?' It started two sessions ago. I've been going to dialysis for about five months. Of lately, I wanted to leave after two hours. So the doc looks at me, asks me some more questions, then he said, 'It sounds like you have infections.' So I said, 'OK, doctor.' They sent me up to the fifth floor. I went along with it. I don't make no waves. I was just trying to express myself. They gave me more medicine to take. The doc up here said I'll be going home soon if nothing materializes with X-Rays I had. The doctor on the ward, after I explained what I said downstairs in dialysis, the doc looked at me and said, 'It's a four-hour treatment.' So I said, 'OK, I'll deal with it. But I just wanted to explain myself.' He said, 'There's nothing wrong with expressing yourself.' So that's where you found me. They brought me here by transportation. I'm not playing games now. I just wanted to express how I felt. I'll go along with the program."

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 12, 2002

Brief phone conversation with Shooby about a reporter from the New York Times wanting to interview him for the New Jersey section. That excited him very much. "The New York Times wants to talk to me?," he sputtered incredulously. I promised to help arrange the interview.

Shooby disclosed that he's "taking all sorts of pills," and doesn't know when he'll be released.

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 20, 2002

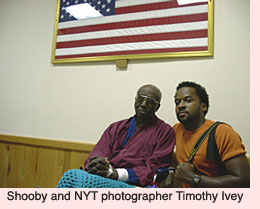

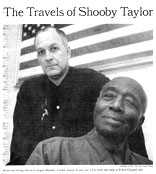

VA Hospital, East Orange, NJ -- Shooby's New York Times photo op. Lensman Timothy Ivy snared the assignment. (The story is being written by Marc Ferris.) By the time I arrived (with Jeff Winner along for a return visit with Shooby), the VA's public affairs specialist, Mary Therese Hankinson, had rearranged furniture in a small 5th floor lounge to accommodate the session. Shooby sat in his wheelchair beneath a huge framed-under-glass American flag, as Tim checked lighting and snapped test shots.

VA Hospital, East Orange, NJ -- Shooby's New York Times photo op. Lensman Timothy Ivy snared the assignment. (The story is being written by Marc Ferris.) By the time I arrived (with Jeff Winner along for a return visit with Shooby), the VA's public affairs specialist, Mary Therese Hankinson, had rearranged furniture in a small 5th floor lounge to accommodate the session. Shooby sat in his wheelchair beneath a huge framed-under-glass American flag, as Tim checked lighting and snapped test shots.

I joked with Shooby while explaining to Hankinson the nature of the man's music -- never an easy process to the uninitiated. She was genuinely intrigued. Tim asked if Shooby had sung blues. I said "no," and Shooby loudly exclaimed, "I scatted with EVERYTHING -- country, gospel, jazz .!"

"Mozart," I interjected. "Yeah," Shooby replied, "Mozart!"

"Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Babs Gonzales, Johnny Cash," I added. "Only none of them knew it."

Shooby asked if I'd posted songs from the Johnny Cash tape on the internet, as he'd urged during our previous get-together. Told him I didn't have a chance to transfer that cassette to CD. He asked my opinion of the Cash material, and I candidly -- and honestly -- teased him that it wasn't his best. His performances vary in quality, I pointed out, with some better than others. The Johnny Cash stuff was interesting, but his scatting was not necessarily well-suited for each song. Whereas the Miles, the Charles Earland, and the Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis tracks were "pure genius."

Shooby asked if I'd posted songs from the Johnny Cash tape on the internet, as he'd urged during our previous get-together. Told him I didn't have a chance to transfer that cassette to CD. He asked my opinion of the Cash material, and I candidly -- and honestly -- teased him that it wasn't his best. His performances vary in quality, I pointed out, with some better than others. The Johnny Cash stuff was interesting, but his scatting was not necessarily well-suited for each song. Whereas the Miles, the Charles Earland, and the Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis tracks were "pure genius."

Hankinson's curiosity heightened, and she seemed delighted at learning of this patient's colorful past -- and that in his twilight years, he was earning recognition for his talents. She suggested that Taylor's music could be played during patient recreation periods. I cautioned her that Shooby's recordings might be harder for some patients to take than their meds: "Many people might not understand or appreciate it." I promised to send along a CD, and advised that she audition it before any public airing. I'm not sure how well the "You Were Only Fooling" intro -- "Story of my life. You lied, you bitch!" -- would go over in patient rec. Or, for that matter, Shooby's relentless vocalese over "Folsom Prison Blues."

As Ivy began the serious photography, I witnessed Shooby undergoing an interesting metamorphosis. The scatman sat -- poised, confident, at ease, staring down the camera. Didn't say a word. His head positions and facial expressions were portrait-ready, as if having his picture taken by the New York Times was a most natural occurrence. Or perhaps something he'd waited for his whole life, and he was basking in cosmic justice.

Tim snapped 50 or 60 pics of Shoob, then directed me to stand behind the wheelchair as he clicked off another 10 or 12. I returned the favor, snapping a few of Shooby with Tim, Jeff, and Mary Therese.

Tim snapped 50 or 60 pics of Shoob, then directed me to stand behind the wheelchair as he clicked off another 10 or 12. I returned the favor, snapping a few of Shooby with Tim, Jeff, and Mary Therese.

Chatted after the session. Asked Shooby if he was watching the World Series. "No!," he proclaimed. "I'm too busy! Very busy." His recent schedule included a movie screened for patients the previous evening (he couldn't recall the title), church services on Sunday morning, going outside to smoke cigarettes, diagnostic tests, more cigs, and such. I told Hankinson that during a recent four-hour dialysis hook-up, Shooby had gotten "bored" after two hours and demanded to be unhooked. "I wasn't bored," he clarified. "I was just restless, and irritated." In fact, it was this behavior that alerted the physician to the infection that occasioned his hospitalization. No one had any idea how soon before he'd be released back to the nursing home.

It was time to clear out, so we slid the furniture back in place and shook hands with Shooby before he was wheeled back to his room.

As Jeff and I headed for the elevator, we encountered a burly young hospital aide in scrubs. The gent glanced in Shooby's direction with an amused look. "Y'know that guy?," I asked. "Sure," he smiled, and said something, the gist of which was that Shooby's a real character. Was he aware of the musical angle? He nodded affirmatively. The aide didn't know the specifics, but tacitly acknowledged that Taylor's heyday was generations ago, a propos of which he added, "We've got one of the original Ink Spots upstairs."

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2002

Today, The New York Times (NJ edition) published Marc Ferris' lengthy article, "The Travels of Shooby Taylor." --> Click Here To Read Article <-- Ferris had heard the Scatman's idiosyncratic stylings and become smitten. When freelancer Ferris discovered that Taylor lived in NJ, he pitched an article, and despite Taylor's marginal public profile, the Times editors agreed. I sent Ferris more of Shooby's music on CDR, and the journalist subsequently interviewed Taylor, Rick Goetz, Craig Bradley, and me by phone.

Today, The New York Times (NJ edition) published Marc Ferris' lengthy article, "The Travels of Shooby Taylor." --> Click Here To Read Article <-- Ferris had heard the Scatman's idiosyncratic stylings and become smitten. When freelancer Ferris discovered that Taylor lived in NJ, he pitched an article, and despite Taylor's marginal public profile, the Times editors agreed. I sent Ferris more of Shooby's music on CDR, and the journalist subsequently interviewed Taylor, Rick Goetz, Craig Bradley, and me by phone.

Mid-afternoon in Hoboken, I picked up two copies of the bulky Sunday edition and stopped at a local copy shop for a dozen full-sized xeroxes before driving to the nursing home. Taylor, I was informed, had been moved to a different room on the third floor. I found him sitting in his wheelchair in the corridor, grumpy because I'd arrived a half-hour later than anticipated. I apologized (though I hadn't specified an exact ETA), and opened the paper to display the article, which I assumed would mollify him. Shooby grunted his approval, but insisted he'd read it later. Right now, he needed a smoke.

I wheeled him into the dining hall -- a birthday party was in progress -- and through two smudged glass doors into the adjacent parlor, an all-purpose TV-bingo-smoking lounge. On the box, Whoopi Goldberg capered in Sister Act. A few slack-jawed residents facing the tube appeared outwardly indifferent to Goldberg's shenanigans. Visibility in the enclosed space was reduced to five feet from nicotine smog. Shooby pulled out a pack, and lit up.

"Now is my favorite brand," he said, "but I smoke anything. Except cigars."

He explained that the surgical incision for the dialysis IV shunt had become infected, hence the hospitalization. His stammering seemed more pronounced than during previous visits. Possibly meds, but I didn't ask. He had some questions about Rick's and my plans to release his music, wondering if we'd put out tapes. I explained that CDs were the format du jour, but that copyright issues might prevent legitimate commercial release of his music. Told him that the solution might be to post his recordings online and make them freely available by download. Having had no experience with the internet, he had difficulty grasping the concept. He asked me what "don-com" meant, as in "Shooby don-com." Not an easy technology to explain without visual aids, but I tried. He mostly nodded, which presumably signified hopeless incomprehension.

What about "that gal on TV who's on the afternoon, with all those people on it? Can we get me on her show?" Wasn't certain who he meant, so I offered, "Oprah?" "Yeah, her!" I remarked that it would be a long shot, but that we'd never expected the Times to show interest so soon.

After about a half-hour, I had to leave. Wheeled Shooby back to his room, perched the papers and xeroxes on the window sill, and bid adieu til next visit.

Driving back to Hoboken, I needed two things: 1) a coffee Frappuccino, and 2) additional copies of the NYT article. First -- and last -- stop: Starbucks, corner of Hudson and Newark. Got the Frap, then sat down to "read" several copies of the Times, which were scattered amid the cushy furniture. I overpaid for the coffee -- had done so for several years -- and figured Starbucks (NASDAQ: SBUX) owed me a "dividend," which I was happy to accept in the form of newsprint.

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2002

After my radio program, headed out with Beadie Finzi and Rupert Murray of Spectre Productions, London, to interview Shooby. Finzi and Murray are producing four 3-minute outsider music vignettes for the UK's Channel 4 (other segs will feature Peter Grudzien, Bingo Gazingo, and B.J. Snowden). This visit had been coordinated over several months, and was ultimately contingent on Shooby's medical status. I'd spoken with Taylor at the nursing home on Monday 11/11 to remind him we were coming two days later. But when we arrived at the appointed time (4:30 pm), with lights blazing and camera rolling to document our entrance, we discovered that Shooby had been retained at the VA hospital following dialysis treatment the previous day. A phone call to the VA by Head of Social Services Veronica Anonyuo -- followed by numerous switchboard transfers -- finally got us through to Shooby, who adamantly insisted he was OK and that we should head over for the interview.

At the VA by 5:15, we found ourselves flipped around in a game of bureaucratic pinball, as various receptionists, administrators and nurses gave contradictory instructions. "Sure, go on up," said one, after which another asserted, "No, you can't interview Mr. Taylor without permission from public relations. And they've gone home for the day." From an office on the first floor, to the nurses' station on the fifth, back to another office on the first, back to the fifth. It took about a half-hour to unsnarl the red tape, after which we were cordially cleared for access to the by-now bewildered Taylor, who wondered where we'd gone.

At the VA by 5:15, we found ourselves flipped around in a game of bureaucratic pinball, as various receptionists, administrators and nurses gave contradictory instructions. "Sure, go on up," said one, after which another asserted, "No, you can't interview Mr. Taylor without permission from public relations. And they've gone home for the day." From an office on the first floor, to the nurses' station on the fifth, back to another office on the first, back to the fifth. It took about a half-hour to unsnarl the red tape, after which we were cordially cleared for access to the by-now bewildered Taylor, who wondered where we'd gone.

Finzi and Murray did a fine job keeping Shooby comfortable in his room; they set up with a minimum of furniture rearrangement, and conducted the interview with great affection. They filmed for about 20 minutes, touching upon many of the biographical details covered above. As he'd been during the NYT photo shoot weeks earlier, Shooby was casually jaunty throughout the interrogation. For a man with zero experience talking to the media before August 2002, Shooby seemed surprisingly smooth and at ease.

Finzi expects the vignettes to air in early 2003. Details forthcoming.

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 2002

My lovely outsider music-digging girlfriend, Barbara Economon (a.k.a. "Mrs. Monkey"), from Minneapolis, was visiting for an extended weekend. On the agenda for today were consecutive visits to: 1) Sandor Weisberger (Brooklyn), former cohort of gone-missing "reddio drammer" icon Judson Fountain; 2) Shooby (Newark); and 3) my 93-year-old Aunt Minna (Irvington), who we took for dinner.

We drove to the nursing home, only to be informed that Shooby was back in the hospital. So Barb and I shuttled up Central Avenue through East Orange to the VA. We checked in at the 5th floor nursing station. I was now a familiar face to the staff, who waved us on to Room 282, where we found Shooby horizontal, in brown flannel jammies. He graciously welcomed us, and Barb was delighted to meet the living legend. It was a brief visit, which mostly consisted of an update on his medical condition, Barb lavishing praise on him for his music, and photo ops. Several pics were taken with Barb's home friend and traveling companion, Al-Bear, and a furry blue canine, dubbed Sandog, which had been gifted to Barb by Sandor Weisberger.

So Barb and I shuttled up Central Avenue through East Orange to the VA. We checked in at the 5th floor nursing station. I was now a familiar face to the staff, who waved us on to Room 282, where we found Shooby horizontal, in brown flannel jammies. He graciously welcomed us, and Barb was delighted to meet the living legend. It was a brief visit, which mostly consisted of an update on his medical condition, Barb lavishing praise on him for his music, and photo ops. Several pics were taken with Barb's home friend and traveling companion, Al-Bear, and a furry blue canine, dubbed Sandog, which had been gifted to Barb by Sandor Weisberger.

Despite his occasional cantankerousness (nowhere in evidence today), Shooby really does appreciate visitors, and expresses his gratitude to all who come to pay homage.

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 15, 2002

Called Shooby at the nursing home around 6:00 pm. He was agitated. I'd promised to phone the busy week before, but the few times I dialed, he wasn't available. One instance when he was around, a nursing home aide called me with a number to reach William in the dining room. At the time I was on a lengthy long-distance call, after which I had to leave for an appointment. This chronic "neglect" made him very cranky.

He reiterated (per a prior conversation) that his relationship with his son "had gone sour." They were not on speaking terms. No details.

In late November, while convalescing at the nursing home, he'd anticipated a problem paying the December rent on his downtown Newark apartment. Not a financial problem -- a logistical one. Apparently he needs -- or thinks he needs -- to pay in person. I'd advised that because he was under clinical care and subject to periodic treatment at the hospital, surely the building management would understand if, under the circumstances, he mailed his rent. No, he insisted, he had to deliver the check in person. Several weeks before he had asked me to drive him, but I explained that I'd be in Atlanta visiting my parents on the date he planned to drop off payment.

Now I asked how he'd accomplished the delivery. "I took a cab," he said. "And the driver was very nice So I took care of him. Y'know, a few dollars. You gotta take care of people when they help you."

He'd had a bad incident with a nursing home aide, and resented the way he'd been treated. Again, no details. He was angry, and groused that he wanted to be "transferred out of here." Where to?, I asked. "Home. Aw, man. HOME!" Said he was tired of the "bullshit" at the nursing home, though I suspected his irritation was temporary. For the most part, he had not previously complained about his treatment at the facility, and everyone I've met at Newark Extended Care is pleasant, patient, and cooperative. But he insisted he was fighting to get out. "You gotta be a soldier. A soldier!," he emphasized.

If he went home to his apartment, who would take care of him? "I take care of myself," he asserted. "Oh, man! You gotta be a soldier. Oh, come on, man!" He was frustrated that I didn't get it.

He hoped my family was OK. "Everybody's got problems," he offered, a propos of nothing. "Even the preachers. Even the preachers. I went to church this morning, and I testified. We all gotta pray. Pray, pray, pray."

He then did something I'd never heard him do during any previous encounter, in person or on the phone.

He sang.

No, never alone

No, never alone

He asked me never to leave me

Never to leave me alone

No, never alone

No, never alone

"I testified, that's what I did. In church, this morning. I got up and sang."

He remained volatile, and seemed impatient being on the phone. He'd deliver a monologue about something that'd ticked him off -- the nursing home aide, his son, my failure to call -- then abruptly interject, "So, what do you have to say?" I didn't know how to respond except to sympathize or apologize, so I tried small talk. I asked for details about his "sour" relationship with his son. That sparked another outburst, and he refused to elaborate. "If I asked you about something with your family, that's none of my business. If that's all you want to talk about -- my son -- I'll hang up now."

He was clearly peeved at my not having phoned for several weeks. He was downright ... paternal? Evidently, in the wake of his falling out with William, Jr., I was (unwittingly) assuming the role of surrogate son.

His testiness gathered momentum for several exasperating minutes, before we brought the exchange to a close. He thanked me for phoning, and offered one final reminder: "Oh, man. You gotta be a soldier!"

MONDAY, DECEMBER 16, 2002

The phone chirped me out of bed at 8:00 am. I don't appreciate calls at that hour -- that is, while I'm sleeping.

The phone chirped me out of bed at 8:00 am. I don't appreciate calls at that hour -- that is, while I'm sleeping.

A nursing home staffer instructed me to call Shooby in the dining room, which I did. In a semi-belligerent tone, he wanted to know if I had any money for him (I didn't; was I supposed to?); he hoped my family was OK (a propos of nothing); and he said the nursing home administrator agreed to see him on Thursday about a release.

The money question -- maybe he's under the impression we're selling his music -- which, I clarified, we're not. He had recently been paid an advance for his tracks on Songs in the Key of Z, but neither album has sold enough to warrant additional royalties to the artists. Taylor had also been paid cash by Channel 4 for his involvement in their filming. Perhaps he now expects some sort of regular payment. I don't know. I was too groggy to pursue the matter.

He stuttered a loud "Thank you" for my feeble responses, and said, "OK, that's all. Good-bye."

My family is fine, but I didn't need to be roused out of a warm sleep on a cold morning to be offered such salutations. And I'll be shocked if the nursing facility entertains the notion of sending Shooby back out on the street.

Ironically, my real father is in a nursing home, and he doesn't call at ungodly hours with perplexing assertions.

I crawled back under the quilt to capture a little more shuteye.